When people find out that I homeschool my children, they almost always say something along the lines of, “I could never do that. You must be a really patient person.”

Most of the time, I respond that I wasn’t patient when I started (my husband can vouch for that), but that my patience developed over the years. I don’t go into too much detail because I’ve discovered that most of these people don’t really want to know how to become more patient. They’re just grabbing onto the first excuse they can think of to explain why they can’t (read: don’t want to) homeschool their children.

But the question of patience is an interesting one. My mother-in-law has commented many times that she is amazed by my patience with my children. Please don’t be fooled by that; I am not always patient with them. In fact, in certain situations, I have to send myself into time-out so I don’t wring someone’s neck (usually that someone is a teenager). But I do think that I have more patience than I once did, thanks to many years of trying to get my children to understand concepts and ideas because I want to help them learn. It is so rewarding to see the light go on when a challenging idea becomes understandable. That light won’t go on if I’m breathing down my child’s neck.

Early on, when trying to explain a concept to one of my children, I would start asking questions to make them think. But soon I’d find myself clueing them in on the answers right away because I got tired of waiting for them to say the right thing. Of course, they weren’t learning anything when I fed them the answer. The next time the subject came up, I could see that they didn’t know anything more this time than before I’d explained it. The answer wouldn’t make sense to them unless it came from their understanding, not my spoon-feeding method.

So I learned to wait for them to catch on. When they’d ask me a question, I’d answer it, and come back with a few of my own to make them think a little harder. Then instead of coaching them to the correct answers, I just waited. Sooner or later, they’d figure it out.

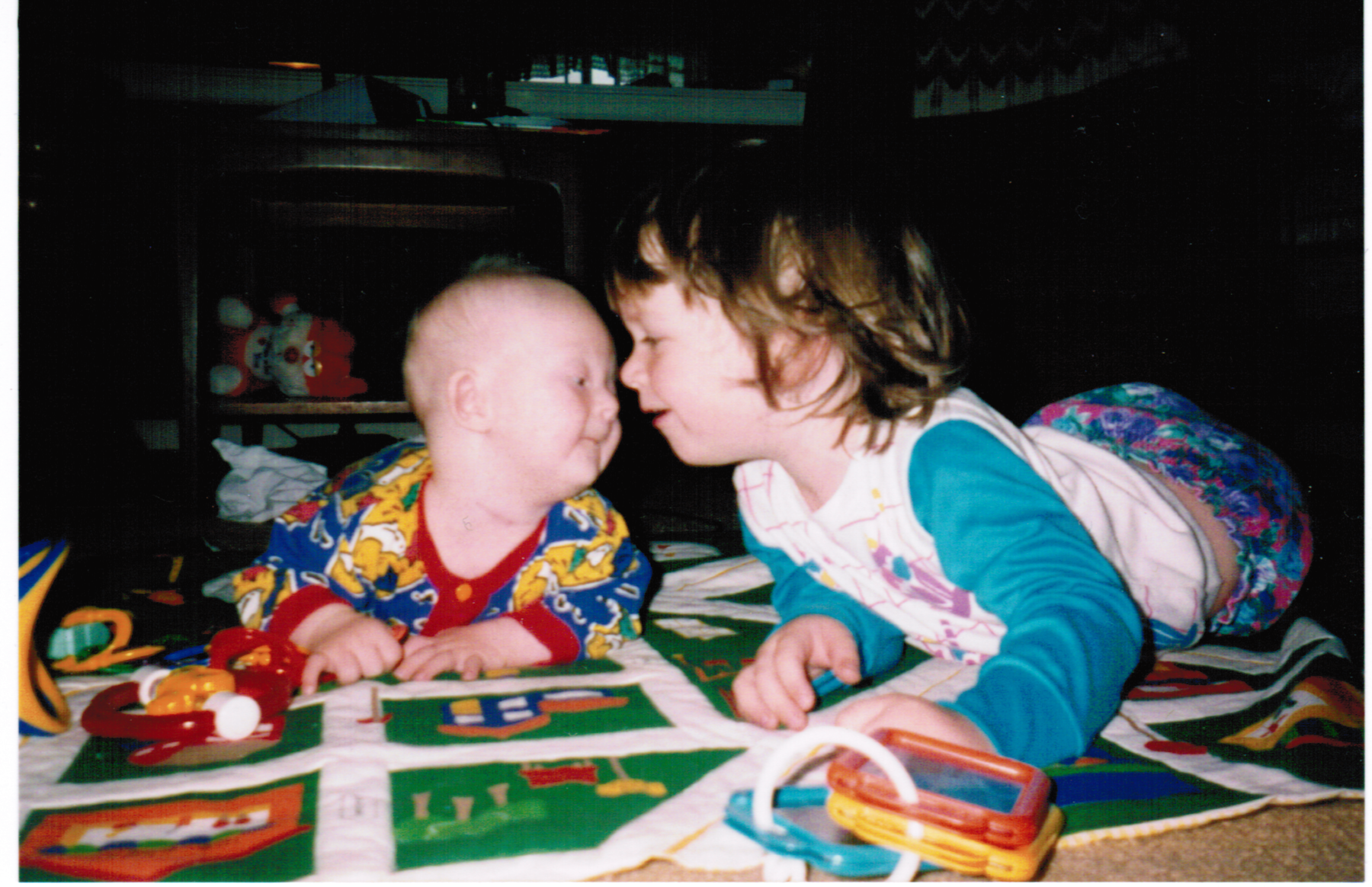

After we’d been homeschooling for several years, I was given a new opportunity for learning patience: our son Josh was born with Down syndrome. In most areas, it took him far longer to learn things than it had taken his siblings. He didn’t crawl until he was 1, and didn’t start walking until 21 months. He’d been in physical therapy since he was tiny, but I’m not sure whether he would have crawled or walked later without it. What I’ve seen with him is that he will not do something until he is ready, and in this way he is much like his brother and sisters. He is my graduate study in the School of Patience.

For example, he did not become toilet-trained until he was seven. We tried coaxing, training and occasional forcing him to use the toilet starting at age three. We bought him potty books and a video. We even tried bribing him with M&M’S®. But he wasn’t ready yet.

When he was five or six, he started using the toilet once a day or so. When he was successful, he would make the general announcement (“Poo-poo! Poo-poo!”), and cheering and applause would break out from every corner of the house. Still, it would be well over a year before he could go without diapers all the time (and probably two or three years before he stopped demanding M&M’S® after each successful bathroom visit).

What a golden opportunity toilet-training him was for teaching us about patience. Nothing we did spurred him on. But when he figured it out, the triumph was all his.

This concept also holds for children who are not mentally delayed or disabled. For example, when a teenager finally figures out quadratic equations, it’s his victory. Sure, Mom and Dad have answered numerous questions, most more than once, and each was a stone in the path leading up to the day when he figured out the concept. But he’s the one who succeeded in grasping the concept.

Now imagine if each time he’d asked his parents a question, they’d responded with a sigh, or worse, with anger (“How many times do I have to explain this to you?”). That would have discouraged him from asking any more questions, and it would have taken that much longer for him to pick up the concept. Or, he might never have figured it out. How sad if he was just one question away from understanding, but was afraid to ask that question.

Some kids need to ask more questions than others, and that can be very wearing on the homeschooling parents who spend their days coming up with the answers. It’s important for us to remember that each question brings the child closer to the point of understanding. Allowing him to reach that point, no matter how many questions it takes, is something that can’t be done in formal school, because the logistics of teaching a group don’t permit it. That’s one of the reasons homeschooling is so successful: the child can move at his own pace, with the support of an adult who will answer his questions and patiently wait for him to “get it,” so that he can move on. A classroom teacher can’t possibly do that with a roomful of students.

The longer you homeschool, the better you get at patiently answering the same question many times. You also get better at waiting for the answers to questions you’ve asked in order to make your child come to a certain conclusion. Your patience in such matters greatly benefits each of your children.

I wish I could tell you that the patience you develop over years of homeschooling translates into more patience in other areas of your life, but I can’t. Ask my son Peter, who had to keep me calm throughout 90 minutes in line waiting for him to get his ID at college registration ($26,000 a year, and they can only afford one ID machine?). Or you could ask those people who drive in front of me at 10 mph below the speed limit; I’m on them like a cheap suit. I guess it’s going to take more than years of homeschooling to make me into a totally patient person.

(Excerpted from The Imperfect Homeschooler’s Guide to Homeschooling. Learn more about this book HERE.)